Japan’s July 2025 upper house election saw emerging parties make considerable progress at the expense of traditional parties. The fervent enthusiasm among supporters of smaller parties has been likened to the way fans back their favorite performing artists or fictional characters.

Gauging the Depth of Political Fandom

The election held on July 20, 2025, for Japan’s House of Councillors was an extraordinary contest in many ways, overturning much of what we thought we knew about Japanese politics. The outcome of the election, which saw parties like the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) and Sanseitō achieve surprising gains, is in line with what we saw in the gubernatorial contests in Tokyo in July 2024 and in Hyōgo Prefecture in November that year. In the Tokyo election, many expected a two-horse race between sitting Governor Koike Yuriko and Renhō, but it was the relatively unknown Ishimaru Shinji, a former mayor of the Hiroshima Prefecture city of Akitakata, who leapt into second place in the voting. In Hyōgo, meanwhile, Saitō Motohiko retook the governor’s office despite having left the seat earlier in the year following accusations of malfeasance, doing so with an even higher vote count than in his previous election.

One thing all these elections had in common was the presence of surprisingly fervent support for these politicians, going well beyond what was evident for the established parties and candidates. Indeed, a look at social media posts by supporters of the DPFP and Sanseitō ahead of the upper house election this year, or of Ishimaru and Saitō in last year’s gubernatorial contests, shows a level of passion not seen among supporters of other parties. In recent months Japanese academics have produced a number of papers likening this to oshikatsu, the fervent “support activities” that fans engage in for their favorite performing artists or fictional characters.

On July 16–19 this year, the four days leading up to the upper house election, I led a team that carried out an online survey of 4,109 men and women throughout Japan. To ensure that the survey was as representative of Japan as possible, we set limits on the maximum number of responses for each gender, each age range (set in 10-year increments), and each region of residence. While it was clear that some individuals answered the survey questions without thoroughly reading their content, we included all respondents in our analysis, considering them to be indicative of certain types of voter. (The Osaka University of Economics Research Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the survey.)

The goal of the survey was to empirically gauge the degree of enthusiasm shown by supporters of each political party, with “enthusiasm” being defined in terms of a high level of emotional dedication tied closely to views of the party and its leadership.

In the survey, we asked questions relating to the major political parties and their leaders, measuring the “emotional temperature” of the warm feelings respondents had toward them. With the highest possible level of support set at 100 and the most negative views possible at 0, and an average view of 50, we asked respondents to give scores reflecting their takes on the parties and party heads.

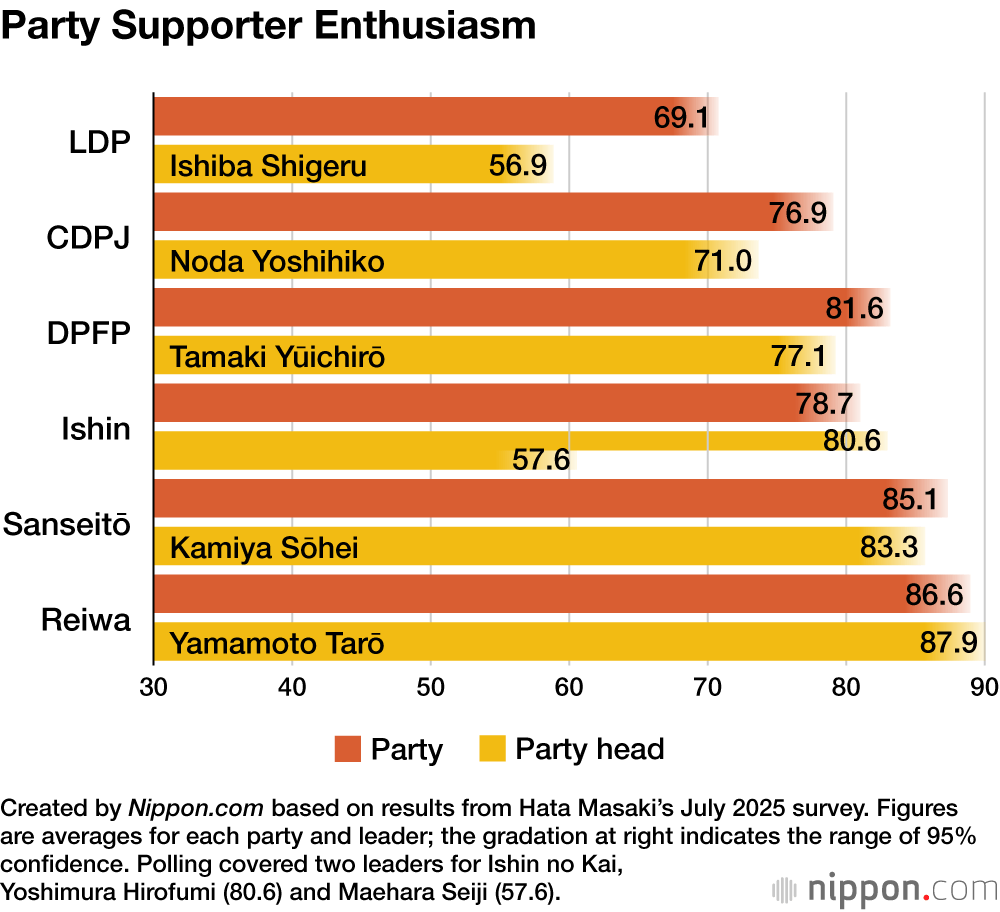

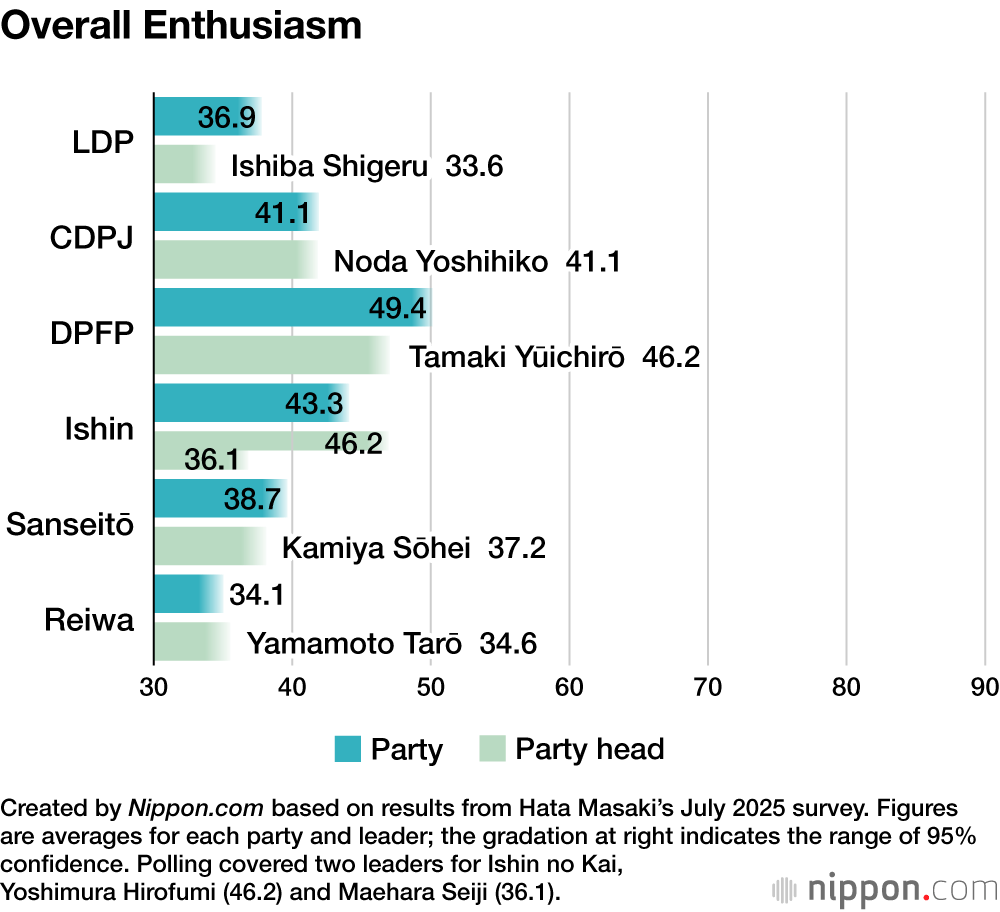

Below I compare the level of enthusiasm that people have for parties and politicians, according to the parties they profess to support. The two figures below display popular enthusiasm for political parties and their leaders. The first is arranged by supporters of each party—at the top of the list, for instance, are the score of 69.1 given by Liberal Democratic Party supporters and their 56.9 enthusiasm score for LDP President Ishiba Shigeru—while the second shows enthusiasm across all survey respondents.

The Low-Enthusiasm LDP and the New Parties’ Fervent Fans

Looking first at the enthusiasm scores produced separately by supporters of each party, we can observe three main trends.

First, supporters of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party show markedly less enthusiasm than those of other parties. Their scores for the party as a whole and its president, Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru, are considerably lower than the scores seen for other parties and heads. In short, in the lead-up to the House of Councillors election this year, even LDP supporters held relatively negative views on their own party.

Second, the smaller parties enjoyed robust support from their supporters. This extraordinary enthusiasm was evident in the high scores for the DPFP (81.6), Sanseitō (85.1), and Reiwa Shinsengumi (86.6).

And third, the gap between support for party and party leader was much more pronounced for the LDP than for the other parties. Fully 12.2 points separate the score for the Liberal Democrats (69.1) and for Ishiba (56.9), while the equivalent gap for the other parties is much smaller: 4.5 points for the DPFP, 1.8 points for Sanseitō, and just 1.3 points for Reiwa. This illustrates that the fans of these parties identify them more strongly with their leaders than do supporters of the LDP.

Indeed, it could even be said that voter support for these parties is driven largely by personality—the fervor fans have for the leaders at their top. Even when scandal strikes, such as when DPFP head Tamaki Yūichirō’s extramarital affair came to light, or when Sanseitō’s Kamiya Sōhei was accused in the midst of the campaign period of financial improprieties, it did little damage to the high levels of support they continued to enjoy. All this bears the hallmark of unswerving oshi, or fandom.

At the same time, this is also a sign that these parties are structured in such a way as to let them evade accountability for any problems they might cause. This is hardly something to welcome in politics. The DPFP and Sanseitō in particular have come under fire for various governance-related issues. If unquenched enthusiasm from their supporters prevents them from developing more proper governance systems, it will likely hamper their efforts to extend their popularity into new segments of the voting population.

Broad-Based Support or Fanatic Backing?

It is additionally worth looking at the gaps between the enthusiasm that supporters of particular parties have (shown by the red bars in the first graph above) and the favorable views of those parties held by the electorate as a whole (the blue bars in the second graph). The greater these gaps are, the more they indicate potentially fanatic levels of support—perhaps even out of line in comparison to societal norms—for those parties.

It goes without saying that self-defined supporters of any given party will be more vociferous in their backing of that party than the public at large. That said, we can identify considerable differences in those spreads depending on the parties in question.

For the LDP, the gap between enthusiasm shown by party supporters and voters in general is 32.2 points. For the CDPJ we have 35.8 points, for the DPFP 32.2 points, and for Ishin 35.4 points. However, there is a considerable leap from these gaps to those seen for Sanseitō (46.4 points) and Reiwa (52.5 points).

While both the DPFP and Sanseitō achieved solid gains in the July upper house election, these numbers show a meaningful difference between the forms of support they enjoyed in doing so. In short, the DPFP support appears to have been largely in line with that shown by voters in general for political parties in general, while the Sanseitō supporters’ enthusiasm stood out as particularly fervent, indicating that voter turnout for that party was more limited to its base in particular.

A New Era to Face for All Parties

All of the above notwithstanding, it needs to be noted that the figures I draw on for the above analysis come from a survey carried out prior to the election. Parties like Sanseitō, which gained fame with the advances it made in the voting, may enjoy increasingly positive views among the public as a result. Indeed, a Yomiuri Shimbun opinion poll carried out on July 21–22, just after the election, found that fully 12% of respondents tapped Sanseitō as their party of choice, making it the most highly supported opposition party, ahead of both the DPFP (11%) and CDPJ (8%). It thus seems likely that prospects for further growth in enthusiastic support for this party could depend on how it unfolds its strategy going forward, in a political landscape where the LDP/Kōmeitō coalition is a hobbled minority government in both of the houses of the National Diet.

And while it goes without saying that the ruling parties face a difficult path, it also needs to be noted that the CDPJ, despite being a relatively established opposition force in a particularly favorable election environment, failed to extend its seats in the House of Councillors—a sign of the severe crisis facing that party.

Space limitations prevent me from going into detail here, but it is interesting to note that enthusiasm for the CDPJ and for Noda Yoshihiko, its leader, are higher than the figures for Sanseitō and Kamiya Sōhei. This means we cannot dismiss the former out of hand as being less liked than the other options. But the election results may display an uncomfortable truth: that it is better to be disliked, so long as people are paying attention to you, than it is to be ignored in the first place.

Going forward, it will be worth watching whether the established parties strive to boost their levels of enthusiastic support, or instead choose to sell themselves as steady, reliable entities worthy of voter turnout. One way or the other, Japanese politics has entered a new phase, and all the players in it must make decisions on how to proceed as it unfolds.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 1, 2025. Banner photo: Sanseitō supporters turn out for a public rally in Yokohama, Kanagawa, on July 19. © Kyōdō.)

Source link

#Passion #Politics #Survey #Sheds #Light #Support #Japans #Parties #Candidates